Adversarial Markets: Stress Tests in Crypto Derivatives and TradFi

Case studies from Hyperliquid to Volmageddon and lessons learned for resilient market design

TL;DR

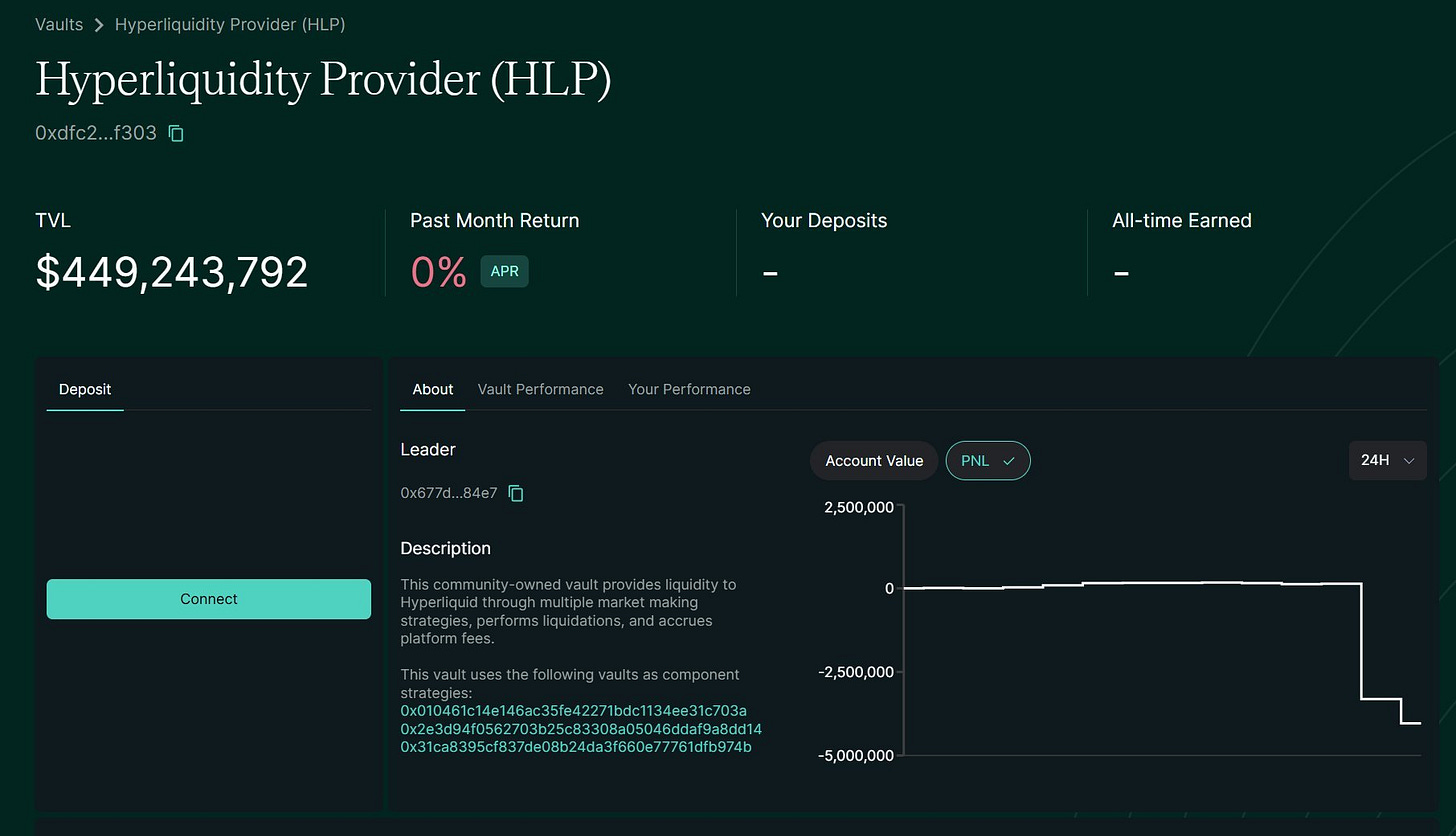

The Hyperliquid exploit, where traders withdrew unrealized gains, exposed critical design flaws in leverage and collateral management, leading to a $4 million loss from the platform’s liquidity vault

Similar structural vulnerabilities have triggered major stress events across crypto and traditional finance, as seen in the BitMEX GDAX index liquidation, OKX’s massive forced unwind, and the “Volmageddon” VIX ETP blow-up

Common patterns include liquidity mismatches, feedback loops from forced liquidations, misaligned incentives, and failures in safety mechanisms like insurance funds

Industry responses have included reforms such as diversified price indices, outlier filtering, tiered margin and position limits, and improved transparency and risk controls

The core lesson: robust market structure and proactive risk management are essential, as adversarial participants will always seek to exploit weaknesses in leveraged trading systems

Introduction

Recent volatility continues to expose structural vulnerabilities in crypto derivatives markets, particularly around leverage, collateral management, and liquidation mechanisms.

The recent Hyperliquid incident, where traders exploited design flaws by withdrawing unrealized gains, highlights these risks clearly. Hyperliquid allowed users to withdraw unrealized profits, effectively amplifying leverage and undermining collateral buffers. When liquidations occurred, the platform's liquidity vault lost ~$4 million. This wasn't just market volatility, it was a design vulnerability exploited intentionally.

Experienced market participants will know this isn’t new.

Past events on BitMEX, OKX, and even in traditional markets reveal similar issues: index manipulations, liquidity mismatches, feedback loops, and risk management gaps.

This post analyzes several of these stress events to identify common patterns, draw parallels across asset classes, and outline practical takeaways for trading firms, exchanges, and projects navigating adversarial markets. The goal is to support better anticipation of systemic risk and to inform more resilient market design.

At Flow Traders, we have observed this adversarial dynamic emerge across multiple stages of the crypto market’s evolution. Unlike traditional finance (TradFi), where trade execution, clearing, custody, and risk management are separate and highly regulated functions, crypto venues often integrate these layers into a single, self-regulated platform.

This adversarial environment is not a flaw. It is an inherent feature of open markets. As such, systems must be designed with the assumption that every weakness will eventually be discovered, stress-tested, and exploited if left unaddressed.

In competitive, permissionless, and mostly transparent markets, traders are naturally incentivized to find edges. Large leveraged positions relative to market depth, gaps in liquidation mechanics, and weaknesses in incentive alignment are all vulnerabilities that participants will target. The challenge for trading venues, and for market participants operating within them, is to anticipate these stresses and navigate them effectively.

With this perspective, we now turn to a series of case studies that illustrate how market structures in both crypto and TradFi have been tested under stress, and what lessons can be drawn for building more resilient leveraged trading environments.

BitMEX’s Rise and the GDAX Index Manipulation

BitMEX, once the most dominant crypto derivatives exchange, pioneered the perpetual swap and normalized high-leverage futures trading. Its early years were marked by rapid growth and, at times, by acute structural vulnerabilities, particularly around how prices were sourced and how liquidations were triggered in volatile or thinly traded markets.

The GDAX Index Event: A Defining Stress Test

One important episode in BitMEX’s history was the GDAX index anomaly of April 2017. At the time, BitMEX’s contract prices were tethered to an index composed of just two spot exchanges: GDAX (now Coinbase Pro) and Bitstamp. This design left the system exposed to single-point failures.

On that day, a single erroneous Bitcoin trade on GDAX printed at $0.06/XBT, an extreme outlier compared to prevailing market prices. Because BitMEX’s index gave GDAX equal weighting, this outlier trade dragged the entire index down to $888.48, even as Bitcoin was trading above $1,180 elsewhere.

The result: BitMEX’s liquidation engine, which was designed to act automatically and without discretion, triggered mass liquidations of otherwise healthy, leveraged positions. Traders were wiped out not by genuine market moves, but by a technical glitch external to BitMEX itself.

This incident exposed several critical flaws:

Lack of Outlier Detection: The index mechanism had no safeguards to filter or exclude statistically implausible trades

Overreliance on Few Data Sources: With only two exchanges feeding the index, any anomaly on one could have a disproportionate impact

Amplification by High Leverage: BitMEX’s 100x leverage meant even tiny index moves could trigger enormous liquidations, compounding the damage

The GDAX anomaly was not just a technical hiccup, it was a systemic stress test. It demonstrated how thin liquidity, insufficiently robust index construction, and high leverage could combine to create a feedback loop of forced selling and market dislocation.

BitMEX’s Response and Industry-Wide Reforms

In response to this event, BitMEX responded by overhauling its index methodology:

Expanded and Diversified Indexes: BitMEX moved to multi-exchange indices, reducing the weight of any single venue and making manipulation or errors less impactful

Outlier Filtering: The platform implemented volatility filters to automatically exclude anomalous price prints from index calculations

Transparency and Communication: BitMEX began publishing more detailed information about its index construction and insurance fund, helping traders better assess systemic risk

These changes set a new standard for the industry. Other exchanges, learning from BitMEX’s ordeal, adopted similar multi-source indices and robust price protections to prevent repeat episodes.

OKX: A Massive Liquidation

The 2018 OKX Incident

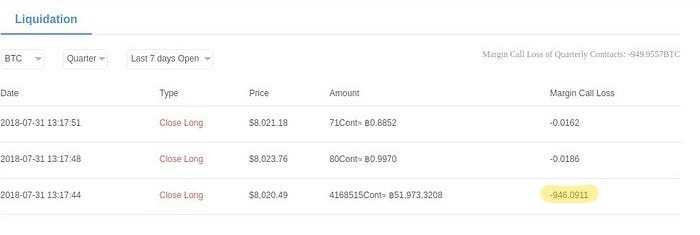

In late July 2018, OKX (one of the largest crypto exchanges) faced a crisis stemming from a single trader’s massive position. This trader amassed an enormous long in BTC futures, 4,168,515 contracts on the BTC0928 quarterly (September 2018 expiry). The notional size was around $420 million, a large exposure even by today’s standards (and extremely large relative to market depth at that time).

What followed was a textbook example of how a large liquidation footprint can impact the market.

The size of the forced sell was so large that it could not be absorbed in the market in one go. OKX’s liquidation engine started unloading the long position into the order book, but liquidity was nowhere near deep enough to offload the liquidation. A substantial portion of the position remained unfilled, even as the market price was driven down by the initial selling wave.

Essentially, OKX had a partial “toxic” position on its hands that nobody was willing to buy without a steep discount. This state of limbo lasted until the weekly settlement, during which time other market participants were keenly aware of the situation. In fact, OKX publicly announced the incident and warned that their socialized loss system might be triggered.

Opportunities for Manipulation

The period between the initial liquidation trigger and the final resolution was tense.

Because everyone knew a large position was being unwound, speculators could try to front-run or capitalize on the forced selling. For example, traders on other exchanges might short Bitcoin futures in anticipation that OKX’s unloading would push prices down. Liquidity providers, on the other hand, might pull their bids, worsening the sell-off.

OKX recognized the danger of price manipulation around the settlement. In their post-mortem they noted “if any attempts of malicious manipulation of the settlement price are found, we will delay the settlement… and manually adjust the price to a reasonable level”.

In other words, they suspected that some traders might attempt to push the price further (or hold it artificially low) at the exact Friday 4pm settlement, to force even greater losses on the residual position or to benefit related positions. OKX was ready to intervene in such case by postponing settlement and overriding the price to something fair, a drastic, but telling, measure.

During this saga, OKX also injected 2,500 BTC of its own capital into its insurance fund. This was done to absorb as much of the loss as possible and minimize the clawback that would hit other traders. Under OKX’s full account clawback system (prior to later reforms), if the insurance fund couldn’t cover a liquidation shortfall, the exchange would take a proportional slice from all users who made net profits that week. This is obviously undesirable and undermines user confidence.

Thanks to the extra 2,500 BTC injection and some manual adjustments, OKX managed to settle the quarter without a huge clawback, though some losses were socialized. It was a wake-up call for the exchange and the broader industry.

OKX’s Reforms Post-Incident

Learning from this event, OKX rapidly rolled out a series of risk management improvements:

Tiered Margin Requirements: OKX introduced a scalable margin ratio system for futures. This mirrors the dynamic risk limit approach where large positions face lower leverage caps. At 10x and 20x leverage tiers, OKX set formulas to increase maintenance margin as position size grew. The effect is that whales can’t max-leverage enormous bets without putting significantly more capital at risk themselves.

Position Size Limits: They also imposed maximum position size per account for each leverage tier. For example, at 20x leverage there was now an explicit cap on how many contracts one account could hold. This prevents a recurrence of a single trader accumulating such a dominating futures position. If one account hits the cap, they simply cannot add more, forcing potential whales to distribute their size (which in practice they may not be able to, if others in the market aren’t willing to take the opposite side).

Taken together, OKX’s changes shifted it closer to BitMEX’s model: more conservative leverage, more transparency about risk (they began publishing insurance fund balances, etc.), and mechanisms to handle outlier events.

For sophisticated participants, this reinforced that liquidity is not just about trading volume, but about the ability of the market structure to handle the unwind of big positions in an orderly fashion. OKX’s episode, widely publicized, pushed the industry standard forward in risk controls.

“Volmageddon” 2018: The VIX Futures Blow-up

What Happened on 5 February, 2018

In TradFi, one of the most infamous market structure vulnerabilities occurred on 5 February, 2018, a day now nicknamed “Volmageddon.”

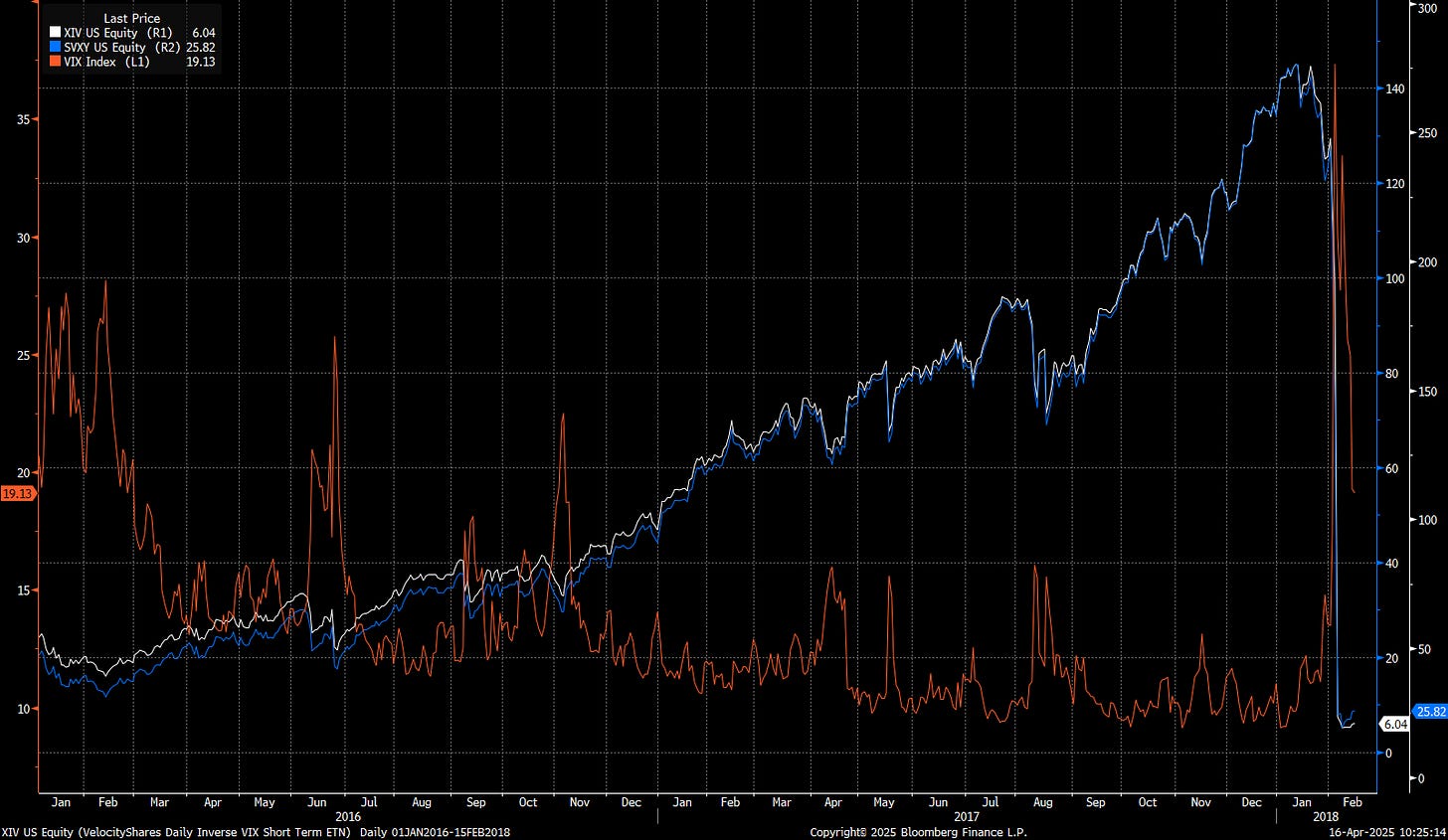

On that day, the U.S. stock market fell sharply (the S&P 500 index dropped ~4% intraday), and volatility spiked dramatically. The Cboe Volatility Index (VIX), which measures market volatility implied by S&P options, shot up from 13.84 to 37.32 percentage points within a week.

This alone was extreme but not catastrophic. What turned it into a crisis was the impact on certain derivatives: specifically, the short volatility ETPs.

Products like XIV (an inverse VIX futures ETN by Credit Suisse) and SVXY (an inverse VIX ETF by ProShares) were designed to deliver the inverse return of VIX futures. In other words, they made money when volatility stayed low or fell.

By early 2018, these products had grown very popular (with over $2 billion in assets), many retail investors used them to bet on calm markets and earn yield from contango in VIX futures.

In the year leading up to the 5 February liquidation event, the combined assets under management (AuM) of the XIV and SVXY products grew from $840mm to around $3.5 billion. Crucially, at its peak, this total represented over 30% of total open interest for the current and forward month VIX futures contracts. In other words, these ETP products had cornered the VIX futures market.

When VIX spiked on 5 February, these products faced a reckoning. By that evening, XIV had lost 96% of its value in a single day, essentially going to zero. SVXY similarly lost around 90%. The chart below illustrates the violent move in the VIX futures (front-month contract) on that day, a surge from the low teens to over 30 in a very short timeframe.

Structural Vulnerability – A Feedback Loop

The core issue was that these inverse ETPs had a built-in rebalancing mechanism that turned out to be lethal under stress. XIV and SVXY were structured to reset their exposure at the end of each day to maintain a target of -1x the VIX futures index. This means that after a day of losses (when volatility jumped), they would need to buy back VIX futures to reduce their short exposure for the next day.

On 5 February, around 4:00pm ET (right after the stock market close), the indicative values of these ETPs were plunging. In order to “remain market neutral” to their mandate, the ETPs had to buy a huge number of VIX futures contracts into the close. But the market for VIX futures was already spiking and somewhat illiquid at that moment, so this required buying drove VIX futures even higher.

That, in turn, further cut the value of XIV/SVXY (since they move inversely to VIX futures), which then required even more buying to rebalance. In effect, a downward positive feedback loop took hold.

The result was a rapid spiral where the ETPs were chasing an ever-rising target, until their values were almost completely wiped out. By about 5:08pm ET, XIV’s intraday indicative value had collapsed, Credit Suisse triggered the acceleration clause to liquidate the note, and XIV was officially terminated a few days later at a redemption value of about $0.05 on the dollar.

Relation to Crypto Market Dynamics

The Volmageddon episode is uncannily analogous to certain crypto liquidation cascades.

Replace “XIV’s rebalancing” with a forced liquidation of a huge short, and “VIX futures” with the asset being shorted, and one can see the similarity: a forced buyer (the rebalancing ETP) kept buying as prices rose, which pushed prices even higher, forcing yet more buying, exactly how a short squeeze liquidation cascade operates.

In crypto, we often see long cascades: a big long gets liquidated and becomes a forced seller, dropping the price and causing others’ longs to liquidate, etc. The VIX case was a short cascade in a sense, the short vol funds had to cover by buying, creating a squeeze on short-vol positions.

It highlighted how leveraged products can destabilize their own market if they hold a large share of it. In 2018, XIV and SVXY were the whale in the VIX futures market, their AUM represented a huge chunk of VIX futures short interest.

When they had to unwind, the market couldn’t cope. This is similar to, say, an exchange where one entity holds a large % of open interest on a futures contract: if that entity is forced out, the market moves drastically.

Aftermath and Changes

The Volmageddon fiasco led to immediate changes.

XIV was wound down entirely. SVXY survived but ProShares halved its leverage (it changed to target –0.5x the VIX futures index instead of –1x, to reduce the size of future rebalances). Regulators and researchers called for better oversight of such products.

This is a lesson highly pertinent to crypto exchanges today: if an exchange offers a product where either the underlying market is relatively illiquid or a few players can corner a large share of open interest, it risks a self-reinforcing meltdown.

In essence, the VIX ETP blow-up taught the TradFi world a lesson very similar to what crypto learned from BitMEX, OKX, and others:

High Leverage + Concentrated Positions = Potential Time Bomb

It underscored the need for position limits and transparency about who holds what. Had there been a rule that no product could hold more than, say, 20% of the open interest of VIX futures, XIV might not have grown so large, and the feedback loop might have been less explosive.

The parallels to crypto are clear, and indeed many crypto exchanges have internalized these lessons (some after experiencing their own mini-Volmageddons, as described earlier).

Common Patterns and Structural Flaws Across Cases

Despite differing contexts, several common vulnerabilities consistently emerge across market disruptions:

Liquidity mismatches and market concentration: When individual traders or products hold positions larger than available market liquidity, it creates systemic risk. Large trades overwhelm market depth during liquidations, magnifying price movements and market fragility.

Feedback loops and cascading effects: Forced liquidations often trigger further selling or buying pressure, creating a cascading spiral that can rapidly drive markets away from fundamental values. This dynamic was evident in incidents involving BitMEX, OKX, and TradFi events like "Volmageddon."

Misaligned incentives: High leverage and poorly structured risk controls can incentivize traders and market participants to engage in manipulative or overly aggressive behaviors. Without proper safeguards, platforms inadvertently encourage exploitation and excessive risk-taking.

Opacity versus transparency: Insufficient transparency masks risks, preventing market participants from accurately assessing vulnerabilities. Conversely, excessive transparency, particularly in decentralized finance (DeFi), can invite targeted attacks by exposing precise liquidation thresholds and positions.

Safety mechanism failures: Insurance funds and auto-deleveraging systems need to be robustly designed and rigorously stress-tested. Failures in these safety nets amplify crises, underscoring the need for continuous evaluation and improvement.

In sum, these patterns underscore that market structure fragility is usually a combination of technical design issues and human/behavioral incentives. When we see a blow-up, it’s rarely just “bad luck.”

Typically, the seeds of the problem were sown long before: an oversized position allowed to grow, an illiquid market listed with too much leverage, a feedback mechanism overlooked, or a misalignment that someone chose to exploit.

Lessons and Best Practices for Exchanges

Drawing on these cases, we synthesize a set of best practices that crypto exchanges should heed to foster a more robust market structure:

Prudent Leverage and Position Limits: Use graduated margin requirements and clear position limits to avoid concentrated risks. High leverage can attract manipulation; moderate leverage helps maintain stability.

Robust Risk Management: Develop risk engines capable of handling liquidations smoothly, using partial liquidations or auctions. Ensure dedicated liquidity reserves (like Hyperliquid’s Liquidator Vault) are well-funded and segmented to prevent system-wide risks.

Restrict Withdrawal of Unrealized Gains: Allow withdrawals only on realized profits, preventing situations like Hyperliquid's exploit where unrealized gains were prematurely withdrawn, destabilizing the market.

Strong Oracles and Price Safeguards: Employ robust oracle systems and set sensible price movement caps to mitigate manipulation, balancing market integrity with genuine price discovery.

Transparency and Monitoring: Provide transparent, aggregated risk metrics and clearly communicate during incidents or interventions. This helps traders better assess risks and enhances trust in the exchange.

Governance and Emergency Protocols: For decentralized platforms, clearly define emergency governance procedures (e.g., multisig or validator votes). Traditional exchanges should also have explicit rules for emergency interventions.

Learn from Traditional Finance: Adopt proven TradFi safeguards like kill-switches for rogue algorithms, stress-testing protocols, and applying lessons from historical crises. Given crypto’s continuous trading, vigilance must be even greater to manage accumulating risks effectively.

Conclusion

The evolution of both traditional and decentralized trading venues shows that even seemingly liquid and technologically advanced markets carry structural vulnerabilities.

Across asset classes, from crypto derivatives to traditional finance structured products, the combination of high leverage, thin liquidity, and misaligned incentives consistently creates systemic risk, especially during periods of market stress.

The lessons from Hyperliquid, BitMEX, OKX, and Volmageddon reinforce a central truth: market structure design is inseparable from system resilience.

Platforms that assume normal conditions will persist, or that traders will act benignly, inevitably find themselves stress-tested by sophisticated participants exploiting structural gaps.

In this environment, traders and liquidity providers play a critical role.

By providing continuous liquidity during periods of stress, enforcing disciplined risk management standards, and maintaining operational integrity, liquidity providers help stabilize volatile ecosystems.

Navigating derivatives markets demands more than just speed or innovation; it demands a constant awareness that under stress, systems will perform no better than their worst-designed components.

The future of sustainable trading venues, both centralized and decentralized, depends on learning from past dislocations, anticipating new forms of adversarial behavior, and embedding resilience deeply into market architecture.

Disclaimer

This content (“content”) has been prepared by Flow Traders B.V. and its affiliates (“Flow Traders”) for informational and educational purposes only. Content prepared by Flow Traders is addressed exclusively to professional and institutional investors (i.e. eligible counterparties) residing in eligible jurisdictions.

Please refer to our full disclaimer here.